(Part 1 of a 4-part Series)

Primary research, which was a dissertation for an MSc in Historic Conservation, offers a fresh and practical understanding that challenges common assumptions and opens new paths. Comparative case study research of redevelopment projects involving complex industrial heritage sites significantly enhances understanding of successes and challenges. This approach offers insights gained from real examples of how integrating old buildings with new green goals evolves in practice. The shift towards recognising the broader social, cultural, and economic dimensions of sustainability, beyond just environmental efficiency, is gaining traction.

Tangible benefits and implications of reuse

The research offers clear, practical lessons drawn from detailed analysis of projects like those in Saxonvale, Frome, Somerset. Two planning proposals were submitted for the same site in quick succession, Saxonvale 1 and Saxonvale 2. Saxonvale 1 was a high density housing and apartment-led proposal and Saxonvale 2 was a lower density housing and mixed-use proposal. Fuller details have been omitted because research is ongoing. Both proposals comprise an application for outline planning permission with all matters reserved for mixed-use redevelopment. The research compared the two proposals and the findings provide compelling evidence for choosing to preserve and adapt old structures by directly comparing different approaches for the same site.

Sustainability advantage

The Saxonvale 2 approach, which focused on the significant retention and adaptation of existing structures within the sensitive area on the boundary with Frome’s Central Conservation Area, was demonstrably more sustainable than Saxonvale 1. The proposals for Saxonvale 1 incorporated high-rise apartments and high density in a historic village setting and involved more extensive demolition. Whereas Saxonvale 2 proposed to retain the existing industrial buildings.

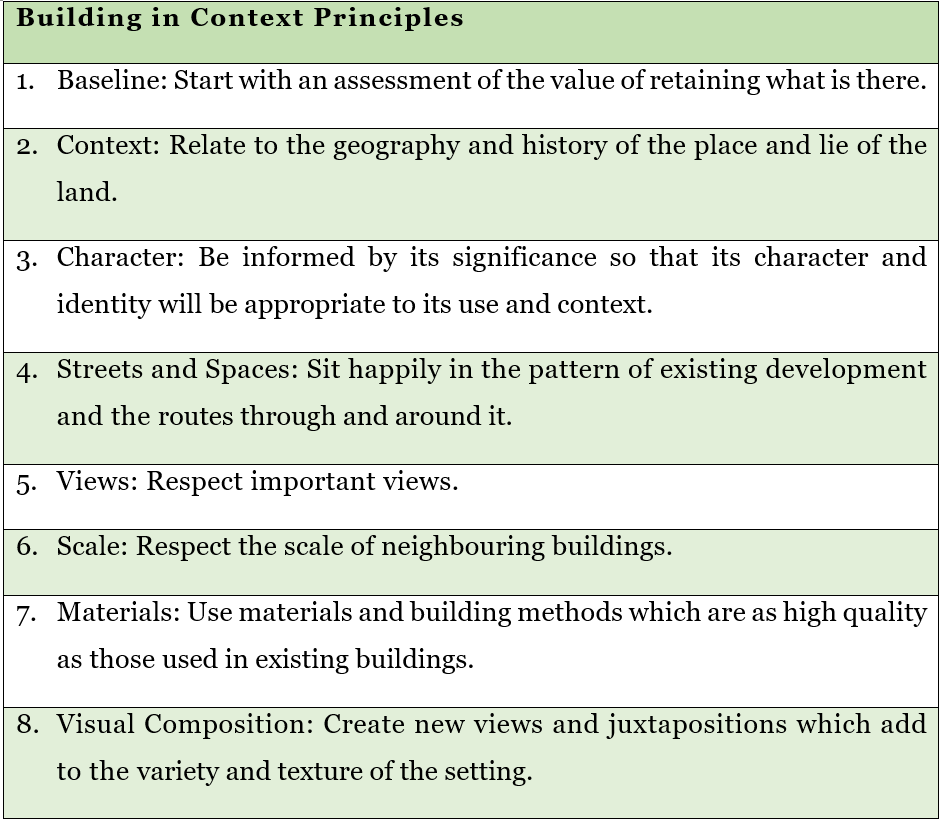

Table 1: Principles for Good Design. English Heritage and Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, ‘Building in context: new development in historic areas.’

(London: English Heritage/CABE, 2001).

Although described as “basically sheds”, industrial buildings were recognised as having good structural integrity and viable potential for refurbishment into commercial spaces, acting as an extension to the town centre. This meant they offered a compelling economic and practical rationale for reuse. The key implication is a substantial environmental saving by avoiding demolition of the embodied energy already invested in materials. This directly contrasts with the higher carbon cost of demolishing and rebuilding that formed part of Saxonvale 1 proposals.

Project viability and acceptance

The research highlights that the reuse-led approach of Saxonvale 2, combined with its robust community engagement, resulted in significantly fewer public objections and a smoother path to approval. This contrasts sharply with the project friction and delays often seen in proposals reliant on demolition. Supporting research based on literature review and interviews, acknowledged that an in-depth understanding of built historic significance is rarely achieved before permission for demolition is sought. This indicates that the practical sustainability benefit of research is not recognised as important in reducing project risk, legal challenges, and associated costs. Instead, permission to demolish is sought before many proposals are designed. In contrast, Saxonvale 2 incorporated the majority of historic buildings winning improved social acceptance and project viability. The management approach avoided friction, delays, and associated costs, in stark contrast to the more contentious outcomes of demolition-heavy proposals.

Misinterpretations and their impact

The research identifies that unclear or inconsistent interpretations of “proportionate” assessment and “sustainable development” can lead to arguments, delays, and proposals that fail to genuinely balance new development with heritage conservation and sustainability. For instance, some interpretations might deem extensive demolition and new-build as “viable” in terms of maximising site development, even in sensitive heritage areas. This misinterpretation implicitly prioritises development yield over heritage conservation and embodied carbon retention, causing public and regulatory objections and hindering truly sustainable outcomes.

For the outcome, read part 2 of this series …

No Responses